Tag: OOP

Python hosting: Host, run, and code Python in the cloud!

Python class: Objects and classes

Introduction

Technology always evolves. What are classes and where do they come from?

1. Statements:

In the very early days of computing, programmers wrote only commands.

2. Functions:

Reusable group of statements, helped to structure that code and it improved readability.

3. Classes:

Classes are used to create objects which have functions and variables. Strings are examples of objects: A string book has the functions book.replace() and book.lowercase(). This style is often called object oriented programming.

Lets take a dive!

Python Courses:

Python Programming Bootcamp: Go from zero to hero

Python class

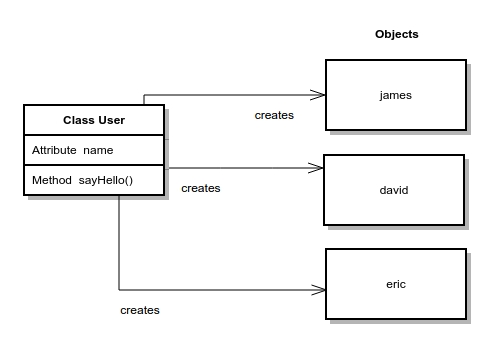

We can create virtual objects in Python. A virtual object can contain variables and methods. A program may have many different types and are created from a class. Example:

class User: name = "" def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def sayHello(self): print "Hello, my name is " + self.name # create virtual objects james = User("James") david = User("David") eric = User("Eric") # call methods owned by virtual objects james.sayHello() david.sayHello() |

Run this program. In this code we have 3 virtual objects: james, david and eric. Each object is instance of the User class.

In this class we defined the sayHello() method, which is why we can call it for each of the objects. The __init__() method is called the constructor and is always called when creating an object. The variables owned by the class is in this case “name”. These variables are sometimes called class attributes.

We can create methods in classes which update the internal variables of the object. This may sound vague but I will demonstrate with an example.

Class variables

We define a class CoffeeMachine of which the virtual objects hold the amount of beans and amount of water. Both are defined as a number (integer). We may then define methods that add or remove beans.

def addBean(self): self.bean = self.bean + 1 def removeBean(self): self.bean = self.bean - 1 |

We do the same for the variable water. As shown below:

class CoffeeMachine: name = "" beans = 0 water = 0 def __init__(self, name, beans, water): self.name = name self.beans = beans self.water = water def addBean(self): self.beans = self.beans + 1 def removeBean(self): self.beans = self.beans - 1 def addWater(self): self.water = self.water + 1 def removeWater(self): self.water = self.water - 1 def printState(self): print "Name = " + self.name print "Beans = " + str(self.beans) print "Water = " + str(self.water) pythonBean = CoffeeMachine("Python Bean", 83, 20) pythonBean.printState() print "" pythonBean.addBean() pythonBean.printState() |

Run this program. The top of the code defines the class as we described. The code below is where we create virtual objects. In this example we have exactly one object called “pythonBean”. We then call methods which change the internal variables, this is possible because we defined those methods inside the class. Output:

Name = Python Bean Beans = 83 Water = 20 Name = Python Bean Beans = 84 Water = 20 |

Encapsulation

In an object oriented python program, you can restrict access to methods and variables. This can prevent the data from being modified by accident and is known as encapsulation. Let’s start with an example.

Related Courses:

Python Programming Bootcamp: Go from zero to hero

Private methods

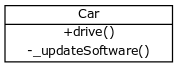

We create a class Car which has two methods: drive() and updateSoftware(). When a car object is created, it will call the private methods __updateSoftware().

This function cannot be called on the object directly, only from within the class.

#!/usr/bin/env python class Car: def __init__(self): self.__updateSoftware() def drive(self): print 'driving' def __updateSoftware(self): print 'updating software' redcar = Car() redcar.drive() #redcar.__updateSoftware() not accesible from object. |

This program will output:

updating software driving |

Encapsulation prevents from accessing accidentally, but not intentionally.

The private attributes and methods are not really hidden, they’re renamed adding “_Car” in the beginning of their name.

The method can actually be called using redcar._Car__updateSoftware()

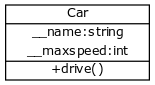

Private variables

Variables can be private which can be useful on many occasions. A private variable can only be changed within a class method and not outside of the class.

Objects can hold crucial data for your application and you do not want that data to be changeable from anywhere in the code.

An example:

#!/usr/bin/env python class Car: __maxspeed = 0 __name = "" def __init__(self): self.__maxspeed = 200 self.__name = "Supercar" def drive(self): print 'driving. maxspeed ' + str(self.__maxspeed) redcar = Car() redcar.drive() redcar.__maxspeed = 10 # will not change variable because its private redcar.drive() |

If you want to change the value of a private variable, a setter method is used. This is simply a method that sets the value of a private variable.

#!/usr/bin/env python class Car: __maxspeed = 0 __name = "" def __init__(self): self.__maxspeed = 200 self.__name = "Supercar" def drive(self): print 'driving. maxspeed ' + str(self.__maxspeed) def setMaxSpeed(self,speed): self.__maxspeed = speed redcar = Car() redcar.drive() redcar.setMaxSpeed(320) redcar.drive() |

Why would you create them? Because some of the private values you may want to change after creation of the object while others may not need to be changed at all.

Python Encapsulation

To summarize, in Python there are:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| public methods | Accessible from anywhere |

| private methods | Accessible only in their own class. starts with two underscores |

| public variables | Accessible from anywhere |

| private variables | Accesible only in their own class or by a method if defined. starts with two underscores |

Other programming languages have protected class methods too, but Python does not.

Encapsulation gives you more control over the degree of coupling in your code, it allows a class to change its implementation without affecting other parts of the code.

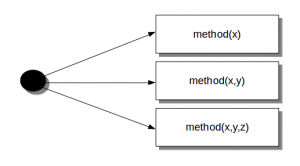

Method overloading

In Python you can define a method in such a way that there are multiple ways to call it.

Given a single method or function, we can specify the number of parameters ourself.

Depending on the function definition, it can be called with zero, one, two or more parameters.

This is known as method overloading. Not all programming languages support method overloading, but Python does.

Related course

Python Programming Bootcamp: Go from zero to hero

Method overloading example

We create a class with one method sayHello(). The first parameter of this method is set to None, this gives us the option to call it with or without a parameter.

An object is created based on the class, and we call its method using zero and one parameter.

#!/usr/bin/env python class Human: def sayHello(self, name=None): if name is not None: print 'Hello ' + name else: print 'Hello ' # Create instance obj = Human() # Call the method obj.sayHello() # Call the method with a parameter obj.sayHello('Guido') |

Output:

Hello Hello Guido |

To clarify method overloading, we can now call the method sayHello() in two ways:

obj.sayHello() obj.sayHello('Guido') |

We created a method that can be called with fewer arguments than it is defined to allow.

We are not limited to two variables, your method could have more variables which are optional.

Inheritance

Classes can inherit functionality of other classes. If an object is created using a class that inherits from a superclass, the object will contain the methods of both the class and the superclass. The same holds true for variables of both the superclass and the class that inherits from the super class.

Python supports inheritance from multiple classes, unlike other popular programming languages.

Related Course:

Python Programming Bootcamp: Go from zero to hero

Intoduction

We define a basic class named User:

class User: name = "" def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def printName(self): print "Name = " + self.name brian = User("brian") brian.printName() |

This creates one instance called brian which outputs its given name. We create another class called Programmer.

class Programmer(User): def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def doPython(self): print "Programming Python" |

This looks very much like a standard class except than User is given in the parameters. This means all functionality of the class User is accessible in the Programmer class.

Inheritance example

Full example of Python inheritance:

class User: name = "" def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def printName(self): print "Name = " + self.name class Programmer(User): def __init__(self, name): self.name = name def doPython(self): print "Programming Python" brian = User("brian") brian.printName() diana = Programmer("Diana") diana.printName() diana.doPython() |

The output:

Name = brian Name = Diana Programming Python |

Brian is an instance of User and can only access the method printName. Diana is an instance of Programmer, a class with inheritance from User, and can access both the methods in Programmer and User.

Inner classes

An inner class or nested class is a defined entirely within the body of another class. If an object is created using a class, the object inside the root class can be used. A class can have more than one inner classes, but in general inner classes are avoided.

Related Course:

Python Programming Bootcamp: Go from zero to hero

Inner class example

We create a class (Human) with one inner class (Head).

An instance is created that calls a method in the inner class:

#!/usr/bin/env python class Human: def __init__(self): self.name = 'Guido' self.head = self.Head() class Head: def talk(self): return 'talking...' if __name__ == '__main__': guido = Human() print guido.name print guido.head.talk() |

Output:

Guido talking... |

In the program above we have the inner class Head() which has its own method. An inner class can have both methods and variables. In this example the constructor of the class Human (__init__) creates a new head object.

Multiple inner classes

You are by no means limited to the number of inner classes, for example this code will work too:

#!/usr/bin/env python class Human: def __init__(self): self.name = 'Guido' self.head = self.Head() self.brain = self.Brain() class Head: def talk(self): return 'talking...' class Brain: def think(self): return 'thinking...' if __name__ == '__main__': guido = Human() print guido.name print guido.head.talk() print guido.brain.think() |

By using inner classes you can make your code even more object orientated. A single object can hold several sub objects. We can use them to add more structure to our programs.